The Three Innovation Types

A personal embarrassment precipitated my appreciation for the three innovation types. I was presenting to a large industrial firm, explaining the latest Innovation Management trends and extolling their use throughout the firm. Concluding my (rather presumptive) presentation, a veteran product manager rebuked me, saying, “Look, it’s obvious you don’t know anything about our industry. Maybe your approach is necessary in tech, but if I save $50 off my BOM through some new process I’m going to sell 10,000 more units. It is as predicable as the sun rising tomorrow. This is how I’ve innovated for 30 years and it’s kept us on top of our industry just fine.” (Left unstated was, “so take this crap and stuff it.”) I sheepishly backed off, murmuring something about disruptive versus sustaining innovation before quickly shifting topics.

The PM was right, of course–he had innovated throughout his entire career without any need for “fail-fast” this, or “customer development” that. Yet my face-saving comment was also accurate. The firm was facing significant threats from new technologies, and what worked for the last 30 might not take them through the next three. The disconnect was that we were using the same term to refer to different innovation types.

Innovation Is Not Homogenous

In his seminal work “The Innovator’s Dilemma”, Clayton Christensen discussed the three main forms of innovation: sustaining, disruptive, and revolutionary (yep, there’s a third!) Each type has specific characteristics which in turn suggest specific management approaches.

The continuous business model set represents the production, marketing, distribution, etc. systems that keep your profit engine running (ie, how the company currently makes money.) Any discontinuity is a different approach that doesn’t fit within the context of that model–retail channels in a direct sales model, for instance. The discontinuous technological set refers to a non-linear shift in capabilities that essentially renders current systems obsolete, while continuous improvements are those which are built upon, and can integrate with, existing processes.

Sustaining innovation is the continuous technological improvement that happens within the context of an existing business model. A Revolutionary innovation is a step-function change in technology, but with some modifications still fits within the firm’s current model. Finally, a Disruptive innovation is a non-linear break in the environment that doesn’t fit within the firm’s current business model.

| Innovation Type | Tech Model | Business Model | Frequency | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustaining | Continuous | Continuous | Common | Significant |

| Revolutionary | Discontinuous | Continuous | Periodic | Substantial |

| Disruptive | Discontinuous | Discontinuous | Rare | Severe |

For a concrete example of each type within a single company, let’s consider Encyclopedia Brittanica (EB). Created in 1768, EB was a general knowledge compendium–the 15th edition was typical at 32,460 pages spanning 32 volumes–used as an authoritative reference on a half-million wide-ranging subjects. EB’s business model was straightforward: editors collected information, compiled it into printed volumes, and sold the sets door-to-door through a commissioned sales staff. This basic model worked essentially unchanged for 225 years, with EB reaching peak sales of $650 million in 1990.

During this time, EB managed considerable innovation–editors improved their data gathering systems, production machinery would advance, distribution mechanics grew more efficient–all geared towards producing a better product at a better price. This is the basic day-to-day grind of business, and it’s where the vast majority of innovation happens. It’s the sustaining innovation, continuous on both the business and technology front, that keeps pace with competitors and maintains market share and growth.

Those two centuries also witnessed many discontinuous shifts in technology: photography replaced lithographs, electric machines replaced the hand-cranked printing press, automobiles replaced horse-drawn carriages for distribution, and so on. These inventions dramatically altered the value chain, and each time EB embraced these developments adjusting to the new capabilities accordingly. However, the core profit-producing model remained intact: the content was still produced by editors, the volumes still printed on paper, and the product still sold door-to-door.

Then, the early 1990’s saw the development of CD-ROM technology. Suddenly what once cost thousands of dollars to produce was now available at less than a dollar in marginal cost and could be distributed via retail channels. While part of EB’s model remained viable–the curation of information–its production and distribution models didn’t match the new technology. CD-ROMs were a disruptive innovation: a discontinuous technological advancement that didn’t fit within their current business model.

Initially unwilling to sacrifice their existing revenues, EB ignored new upstarts like Microsoft Encarta, confident their brand would win the day as it had for more than 200 years. However, after their sales plummeted by 80% in three years, EB released on CD-ROM–but it was too little, too late. The firm that had weathered the American, French and Russian revolutions, that saw the introduction of electricity, the internal combustion engine, and rockets to the moon, that had been the authority for more than two centuries and a scant five years prior experienced the highest revenue in its storied history–was unceremoniously sold for a fraction of its book value in 1996.

Encyclopedia Brittanica innovated continuously for well over two centuries, and during that time they employed the normal tools of business to keep pace with their competitors. Periodically–perhaps once a decade–they would need to embrace some radical invention that required investment and adjustment to give their profit engine a boost. Eventually they hit a disruption that proved fatal, but it’s worth noting it took more than 200 years to reach that point. Most of the time they were doing everything necessary to stay on top of their market.

This is what the PM was trying to tell me. My tactics and techniques were not for the whole company, and certainly not for his business. He lived in the world of continuity; small, incremental progress built on current technology, making everything a little bit better in a well-known market and model. My suggestion to “move fast and break things” wouldn’t get him ahead–it would get him fired. The rebuke was well-deserved.

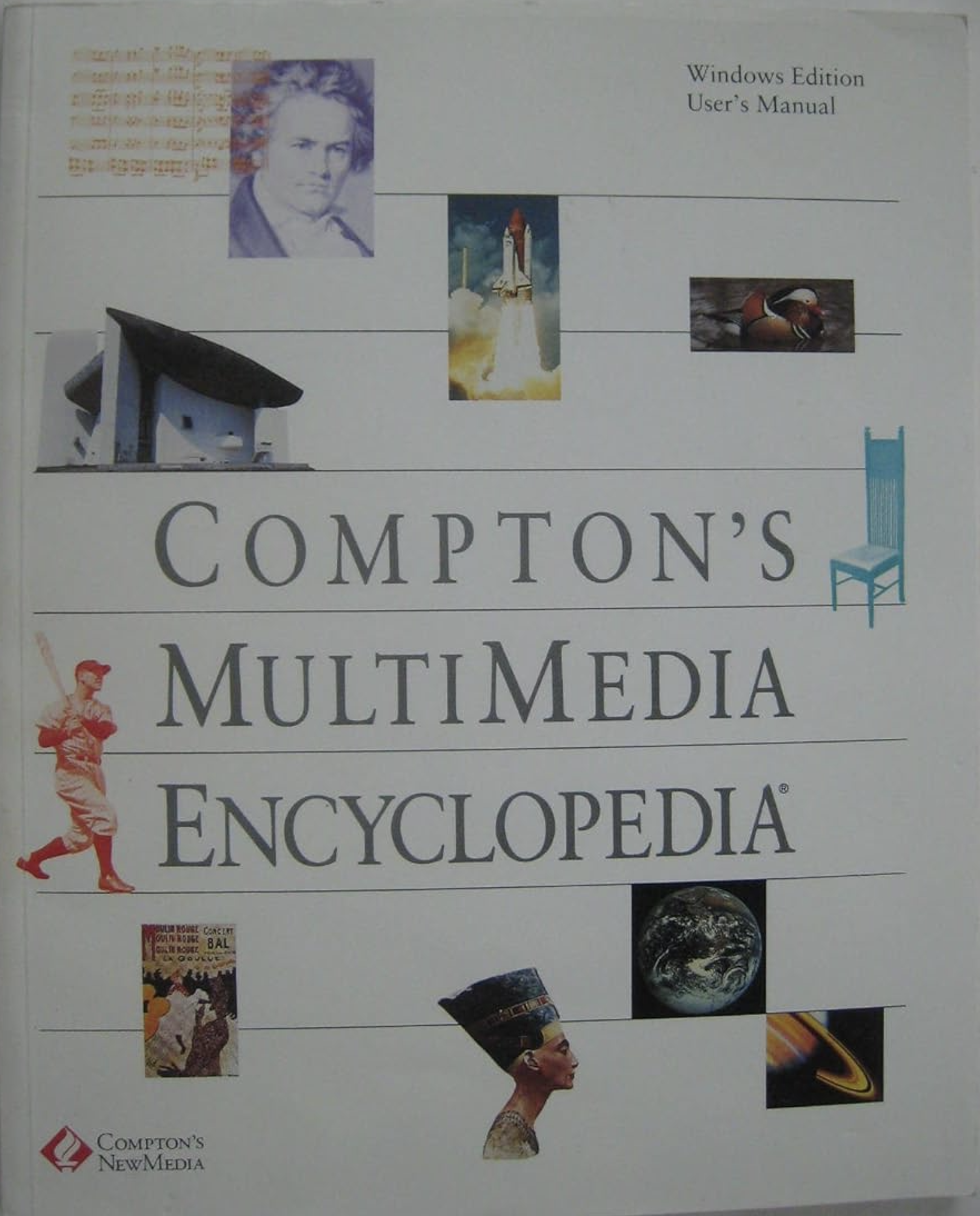

Yet it’s also worth noting that CD-ROM technology didn’t catch EB by surprise–in fact, they actually published the first multi-media encyclopedia on CD-ROM in 1989 through Compton’s, one of their subsidiary publications. But seeing lackluster retail sales–and strong pushback from their own direct sales force–they shut it down. The firm I was presenting to found itself in a similar situation, and the innovation management approaches to avoid a similar fate were relevant; just not as one-size-fits-all solutions for everyone in the company.

Knowing your innovation type is critical to applying the proper management approach: Sustaining innovations should employ traditional linear management techniques like budget forecasting, planning, waterfall production methods, etc, because the degree of uncertainty is low both on the technology and business model fronts. If a new technology shows it can make a better product cheaper, then don’t worry about whether you’re following the latest innovation management trends–just do it.

Revolutionary innovations can similarly employ traditional business planning approaches. Remember that while revolutionary innovations employ discontinuous technology, the business model itself remains roughly constant. So our goal is to test the technology itself, particularly with regard to scale, to make sure the investments in both financial and human capital will be a net benefit. For revolutionary innovations, techniques such as stage-gate and other discrete methods of acceptance testing work well to mitigate downside risk.

Disruptive innovations mean that both the technology and business model face uncertainty, the latter implying that traditional management techniques will be ineffective (ie, the Innovator’s Dilemma). This is where iterative, learning-based approaches shine. They provide a method to test both the technology and business model, providing growth options should the current model suffer, and are specifically oriented to handling the uncertainty that disruption innovations produce.

To determine your innovation type, start with the technology. Again, most technology trends are continuous, so sustaining is always the default position. For discontinuity, look for “hot tech” like drones or blockchain, and consider if the developments have the potential for an order of magnitude improvement in your value chain. Don’t worry if it can’t immediately scale, or if the current price doesn’t justify investment–the goal is simply to identify if it’s at all relevant (drones might not affect your insurance business). If the potential is there, then consider whether or not something in your business model will need to change to accommodate the new technology (ie, as CD-ROMs made retail possible). This process is more difficult than it sounds because firms tend to view the future through the lens of their existing model and are quick to discount things that don’t fit within it. Still, our goal is simply to determine what’s possible, not likely or certain, so don’t worry about every detail and instead view with the widest possible lens.

Alternatively, as a hack ask your sales staff what they think about the new ‘hot tech’. All of them will expect the company to invest in a sustaining innovation–they need that to sell today–and so there will be no complaints. And most will view a revolutionary innovation as the opportunity to close deals competitors can’t, either by offering an awesome new feature or providing the same product at a far better price; so again, you’ll get mostly positive feedback. But few will view a disruptive innovation favorably. They will either see it as irrelevant (it can’t help them make money, so who cares)–or as a threat (this could eat into my commissions–it’s a bad idea). This is precisely what happened to EB. Their sales staff initially ignored and then actively fought against CD-ROMs, and management (all too eager to maintain sales) agreed. Sales is as the top of the funnel and should always be the first consulted, as it gives you the greatest head start on any potential downstream disruptions.

All companies are good at sustaining innovation–those that aren’t simply don’t stay in business (the “Red Queen Hypothesis”). Well-managed companies are able to embrace and effectively absorb revolutionary innovations to maintain long-term success. The truly exceptional companies are those who can manage disruptive innovations and come out the other side. Knowing the innovation type you face guides the management approach that should be employed, and increases your overall chances of success.